Why did we Americans lose our savings habit?

The U.S. dollar was taken off gold in 1973. Since then, Americans’ good personal savings habit has been eaten away by a combination of inflation plus our failure to index savings and wages against inflation. It appears that the federal structure of the U.S. has impeded indexing. Work in the U.S. economy helped expand the economy by a factor of two in real terms, but inequality of income and net worth reached record levels. To do better on indexing and on equality, should we in the U.S. change the way we govern ourselves?

G.M. Kuhn, Ph.D.

St Martin Systems Inc.

August 14, 2010

Introduction

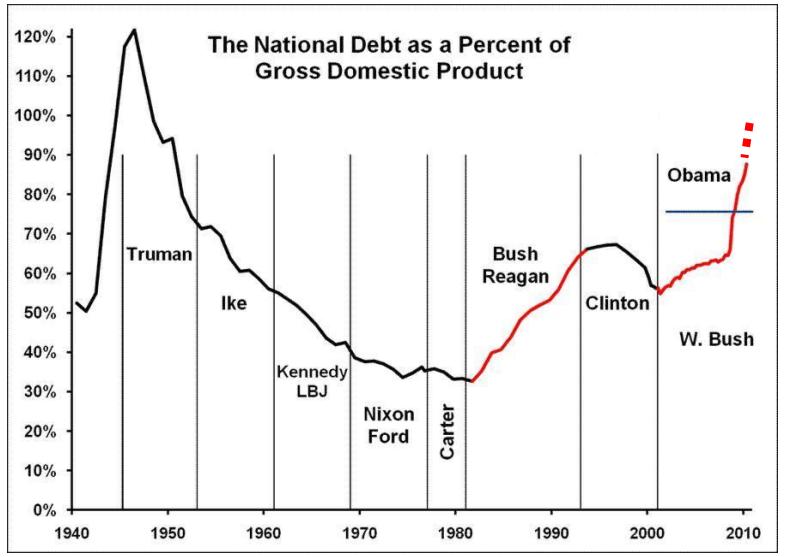

Since Ronald Reagan became President of the United States in 1980, the national debt of the U.S. has tripled as a percentage of GDP.[1] And, recently, the White House estimated that the U.S. national debt will reach 94% of GDP, $13.6 trillion, by the end of 2010 [2].

Figure 1. U.S. national debt as a percentage of GDP. Source: zFacts.com.[1] The dotted extrapolation through the end of 2010 is based on an estimate from the White House.[2]

These two facts made me wonder about both our national debt and our personal savings: have we Americans lost a savings habit that we used to have, and if so, why? Here are some more facts and some questions. I hope they help us to evolve our understanding of this matter.

Taking the dollar off gold enabled us to expand the money supply

Since 1973, the U.S. dollar has no longer been sustained – or constrained – by convertibility to gold. In 1933, that convertibility had already ended for domestic transactions. But in 1973, convertibility to gold was ended even for transactions with other countries’ central banks.[3]

Arguments were offered both against, and in favor of, making this change. Against this change was the argument that there is more confidence in the U.S. dollar if it is convertible to a good recognized as having intrinsic value. Historically, gold played the role of such a good.

Figure 2. Graph showing the final closing “value” of the U.S. dollar for each calendar year from 1954 through 2003. Value is measured in milligrams of gold. Source: Wikipedia.[3]

From this point of view, one disadvantage of removing the U.S. dollar’s convertibility to gold seems clear. Just before the dollar was taken completely off the gold standard in November, 1973, a foreign central bank needed only $38 to buy a troy ounce of gold. But 37 years later, at one moment on Friday, June 18, 2010, you or I would have needed $1,263.70 to buy that same ounce of gold.[4]

In other words, since taking the U.S. dollar off the gold standard 37 years ago, the purchasing power of the dollar, as measured by the amount of gold that it can buy, has fallen to 2.8% of what it was, or equivalently, the U.S. dollar has lost 97% of this aspect of its purchasing power.

However, there were also arguments in favor of taking the U.S. dollar off the gold standard. One argument was this: only so much new gold is found from year-to-year, and the U.S. dollar is the only legal tender in the U.S. economy. If each dollar in our economy must be backed by gold, how could we grow our economy faster than new gold is discovered?

In large part, the price of gold has gone up so much since 1973 because without the constraint of convertibility to gold, the U.S. money supply has grown a lot. In the U.S. economy, and in other economies, so much money has been created without gold, that the same old proportion of interest in gold would now correspond to much more money.

In other words, simply growing the money supply helps give gold its higher dollar-denominated price today.

Here are some specifics. Near the end of 1972, gold hit a high of around $70 per ounce in floating exchanges [3], and the U.S. money supply has grown by a factor of 8 (M2) to at least 10 (M3) since then. [5] The U.S. government stopped publishing M3 but a factor of 10 is available for 2006.

Figure 3. Since 1973, U.S. money supply M2 increased by a factor of 8, and money supply M3 increased by at least a factor of 10. Source: Wikipedia. [5]

If we divide by a money-supply expansion factor of 10, the June 18, 2010, gold price of $1263 becomes $126, and if we then divide by 2 for the ratio of floating ($70) to controlled ($38) exchange rates, today’s price for gold scales back to $63 per ounce, in the controlled, convertible tight money of 1973.

So we can argue that, since 1973, the price of gold has gone up by less than a factor of two, once we remove effects of the expanded money-supply and the old, controlled exchange rate.

Now, people are accustomed to thinking that failures or uncertainties in today’s politics or economics contribute to today’s higher price for gold, and I agree. For some investors, such failures or uncertainties may produce a so-called “flight to quality” including a flight to gold.

In addition, new economic uses of gold, such as its increased usefulness in integrated circuits, may contribute to raising the price of gold as well.

But, the general economic trend has been creating much more money, with the result that there is much more money. This fact by itself contributes significantly to much higher prices being available today, for not much more interest in the relatively limited supply of gold.

And for that I would say, congratulations to us, congratulations for having gotten off the gold standard and for having expanded the money supply, if the total value of our money has grown in real terms, and if the distribution of that expanded supply of money is not problematic. As we shall see, there is much more to say about these two caveats.

Total inflation since 1973 equals an interest rate of 4.35% paid for 37 years

Now, if we are really interested in what has happened to the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar, there are broader measures than gold, measures for example that are based on a basket of goods whose price goes down or up with a so-called “cost of living”.

If the “cost of living” goes up as measured in U.S. dollars, this is not a narrow-based indicator of loss of purchasing power as with gold, this is instead a broad-based indicator, an indicator of what we have come to call “inflation”.

We use the name “inflation” because it now takes an “inflated” number of U.S. dollars to buy that same basket of goods. For most people, such broadly defined inflation is a more relevant indicator than the price of gold, of how much the purchasing power of their dollars may have fallen.

And since 1973, when the U.S. dollar was taken off the gold standard, our rate of inflation, as measured in broad-based terms of “cost of living”, has increased significantly.[6]

How much inflation have we had? Well, to answer that question it would be interesting to know, if we had saved our money in a bank, what annual interest rate would the bank have had to pay us, to match the increase in dollars that is now demanded of us by the past 37 years of inflation?

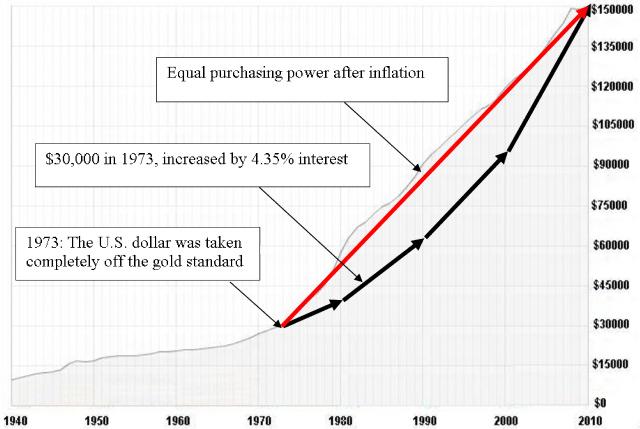

Using cost-of-living data from the U.S. government,[6] I have calculated that an interest rate of 4.35% matches the increase in dollars now demanded of us by these past 37 years of inflation.

To some, an average inflation rate or interest rate of 4.35% may not seem very high. Technically, it means that when we solve equation (1) for the quantity called “Rate”,

Face_Value_Dollars_Later = Face_Value_Dollars_Earlier * exp(Rate * Time) (1)

we get that rate of 4.35%.

But, there is a sense in which 4.35% is a high rate of inflation or interest. If we started in 1973 with, say, $30,000 in the bank, and if inflation averaged 4.35% for the 20 years until 1993, we would already need 2.4 times more money, or $72,000, just to stay at the same purchasing power:

$72,000 = $30,000 * exp(.0435 *20) (2)

And after the 37 years from 1973 to 2010, we would need $150,000, 5 times more money than we had in 1973, again, just to maintain our purchasing power:

$ 150,000 = 30,000 * exp(.0435 *37) (3)

So in the long run, we can now see how high and how serious an average inflation rate, or an average interest rate, of “only” 4.35% really is!

As inflation tilted up, personal savings began to fall

So, what does inflation have to do with whether or not Americans had, and lost, a savings habit?

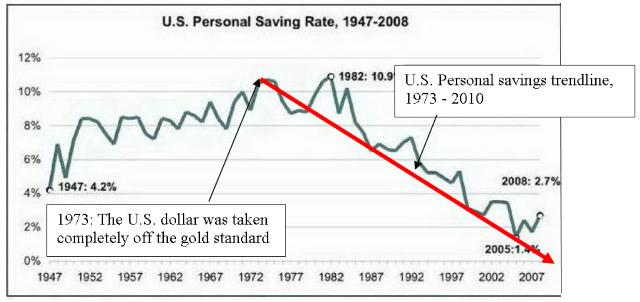

Well, it appears that once the dollar was taken off the gold standard, inflation tilted upward and the U.S personal savings rate began to fall. See Figures 4 and 5 below.

Starting from a 1973 personal savings rate of over 10%, the downward trendline of U.S. savings approaches 0% this year, in 2010, on a path that would take it, if allowed, into negative territory.

I mean, why would we stop when we get down to 0% savings? Instead of merely decreasing our savings, we could continue on, increasing our debt. If saving and investing is good, is borrowing and leveraging possibly even better?

Borrowing and leveraging is what many Americans increasingly planned on, in the hope of better financial results later.[7]

The choice for many Americans was apparently this: save U.S. dollars, which continue to lose purchasing power due to inflation, or borrow, perhaps even more dollars than one has saved, to give oneself a chance of retaining or increasing one’s purchasing power in the future.

Think about it. Would you not be tempted to exchange the certainty of loss in purchasing power in a savings account, for a possibility of gain, namely, that borrowing and leveraging could retain or increase your purchasing power?

Viewed in this light, financial security in a personal savings account is an enemy of marketers of leveraged investments, marketers who could earn commissions or more, if we buy bigger houses with bigger mortgages or take positions on margin, e.g. in financial or commodities markets.

And commercial interests seized the opportunity, offering all kinds of accounts, deals, funds, partnerships and trusts, to tease money out of disappointed savers’ hands. [8]

The marketers’ message has been this: you need to avoid the loss of purchasing power associated with your “savings”. Leverage yourself into some big investment, a bigger house, or whatever, and later on, sell what you bought into, for a significant net real gain.

The enticement of Americans to change their habits in this direction has been unrelenting. But an additional factor was also pushing Americans.

Figure 4. In 1973, the U.S. dollar was taken off gold and inflation tilted upward. The purchasing

power of $30,000 in 1973 is the same as $150,000 in 2010. Source: USA Today.[6]

Figure 5. How the U.S. personal savings rate of 1973 compares to today. Source: Business

Insider.[13]

The savings of working Americans went down for an additional reason as well: our wage increases did not keep up with inflation.[9] After expenses, Americans had less money to put into a savings account. For married Americans, even when both spouses were working, eventually borrowing may have turned from an option into a necessity, to maintain the appearance of a previous, or of an improving, standard of living.[10]

Next, what about retired Americans with a fixed pension or a fixed-size “nest egg”, how were they to maintain their standard of living? What could they do when both 1) savings interest rates at the bank, and 2) cost-of-living adjustments on pensions, did not keep up with inflation, and when in addition banks or brokerages might not give them a long-term leveraging loan? The answer is: their standard of living suffered.[11]

Have you seen the interest rates offered in American banks in 2010, even on Certificates of Deposit (CD’s)?[12] They are nowhere near the 4.35% needed to match the inflation of the last 37 years.

In today’s economy, where could either a wage-earning or a retired American achieve face-value gains of 4.35%? If we invest in, say, U.S. Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) or U.S. Treasury bonds, how much would that help? Well, 10-year U.S. Treasurys may return as much as 3.30%.[14] This rate is better than nothing, but it would not keep up with the inflation of the last 37 years.

Plus, the U.S. government recently granted itself the authority to add a total of almost two trillion dollars to the U.S. money supply, first in a bank bailout [15], and then in a stimulus program.[16] So, what will inflation be in coming years?

Inflation may be low during the current recession but do you think inflation will be higher in coming years? I think so. Hedge funds think so too. Hedge funds currently hold a record short position against 10-year U.S. Treasurys.[17] There is still plenty of time for inflation to return and for the resale value of a bond to shrink, by a maturity date in the year 2020.

So, the graphs on the previous page show very well that we Americans had a positive savings rate and lost it during the inflation of the last 37 years. Now let us look at how mortgage interest rates joined savings interest rates and wages as part of the story.

Home mortgage interest was better indexed to inflation than savings or wages

If the onset of higher inflation was a necessary condition for losing our savings habit, was it also a sufficient condition? No, something else had to not happen, and it did not happen.

When inflation increased, the interest rate that individuals had to pay on home mortgages began to increase. In 1973, the national average contract mortgage interest rate was 8%. By 1980, that average mortgage rate was 12% and by 1982 it reached 15%.[18]

While mortgage rates doubled, why were savings interest rates kept capped at 5.5%?[19] Is there anybody to blame, or what should have been done about that, or what should we yet do about it?

We Americans are a self-governing people. What if, through our U.S. government, we had passed a law that required the savings account interest rate to be adjusted or “indexed” for inflation?

Would higher inflation have cost us our savings habit if we had indexed savings interest rates and also wages more thoroughly?

Did we fail to provide enough indexing against inflation for Americans’ personal savings?

The decisions about the convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold, and about policy affecting the U.S. money supply, were made at a national level.

The U.S. dollar is, after all, a national currency. It is this country’s one and only legal tender. Students of the history of U.S. state- or bank-based notes and currencies may remember that industrialist Peter Cooper railed against local currencies and local banks.[20]

Ever since the time of Peter Cooper, who was a candidate for the U.S. presidency in 1876 on the ticket of the “Greenback” party, there has only been a national currency in the U.S., but as recently as 1999, it was still the states who remained the authority which determined the structure of banking within their borders.[21]

Many of our state-chartered banks used to be mutual savings banks. The U.S. Mutual Savings Bank (MSB) industry started in the early 1800s, “to help the working and lower classes by providing a safe place where the small saver, then shunned by commercial banks, could deposit money and earn interest.”[22]

And please note: we may be talking about small savers and local banks, but we are not talking about risky banks. Even during the Depression of the 1930’s, MSB’s were far less prone to bank runs than either commercial banks or savings and loan associations.[22]

Nor are we talking about small total amounts of money deposited. In 1975, the average MSB had three to four times more assets ($250 million) than the average commercial bank ($66 million) or the average savings and loan association ($69 million).[22]

So, the national government redefined the U.S. currency as a “fiat currency” and increased the money supply, perhaps to good effect. But what were the consequences of leaving control of savings interest rates in the hands of a combination of local bank officers and state-based savings bank regulators, as well as national banking officials?

When local “disintermediation” (withdrawals) from savings accounts caused obvious and predictable liquidity problems for the state-chartered savings banks, and the House of Representatives of the U.S. national legislature published its 1975 report Financial Institutions in the Nation’s Economy [22], appropriate new national regulation was promptly passed, right?

No, it was not. And it took 3 years until savings banks could offer higher interest rates on money-market Certificates of Deposit (CD’s), and then they only offered CD’s for larger savers, savers with $10,000 or more on deposit ($50,000 or more in today’s money).[22]

And it took 5 years and recognition that the savings bank industry was effectively bankrupt before state-based usury laws were pre-empted, by the national Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980.[22]

By then it was too late for many savings banks, and the savings habit of Americans was on its way into the history books.

So, would it be fair to say that the federal structure of the U.S. allowed the national government to redefine the national currency without backing by gold, but impeded the national government from indexing savings account interest rates for protection against the resulting inflation?

This question about the effect of the U.S. form of federalism on the loss of the U.S. savings habit is made more poignant if we look at the smaller amount of money in the average Savings & Loan Association (S&L), but the huge $160 billion cost of bailing out the S&L’s.[23]

Bert Ely provides a list of state or national (he calls them “federal”) policies that contributed to the S&L disaster of the 1980s [23]:

1. Federal deposit insurance did not charge higher premiums on more risk-taking S&Ls.

2. Short-term passbook savings funded long-term home mortgages, a maturity mismatch.

3. Federal Regulation Q (1933) limited savings interest rates and was extended to S&L's in 1966.

4. State-based usury laws locked S&Ls into below-market rates.

5. A federal ban on adjustable-rate mortgages was only taken off in 1981.

6. Federal deposit insurance on state chartered and supervised S&Ls threw losses onto federal

taxpayers if state regulators ran the S&Ls badly.

7. Federal mortgage agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac undercut the S&Ls profits by lowering

interest rates on all mortgages.

8. In October 1979, Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker restricted the growth of the money supply,

causing interest rates to skyrocket.

9. In 1980 and again in 1982, deregulation of the state-chartered S&Ls was not accompanied by

higher premiums for deposit insurance.

10. In the early 1980s the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) allowed S&L losses to be

listed as"goodwill", reducing capital cushions just as deregulated S&Ls took on more risk.

11. The FHLBB allowed badly managed and insolvent state-chartered S&Ls to continue operating,

eliminating the maximum limit on loan-to-value ratios for S&Ls in 1983. After 1983, an S&L

was allowed to lend as much as 100% of the appraised value of a home.

12. These allowances encouraged real-estate developers to acquire their own S&Ls, and grow them

into insolvancy. Developers by nature lack the caution of bankers.

13. Delayed closure of insolvent state-chartered S&Ls increased the Federal Savings and Loan

Insurance Corporation's losses. Over half of these losses reflected the pure cost of delayed

closures - compound interest on already incurred losses. Crooks stealing from the S&Ls then

cost the federal taxpayers money because the S&Ls were insolvent.

14. The FHLBB and the U.S. Government Accounting Office pretended that the cost of bailing out

the S&Ls was lower than it was. A May 1988 estimate of $35 billion to fix the problem was

forced up by the facts to $81 billion just eight months later.

15. An unwillingness to confront the true size of the S&L mess and to anger politically influential

state regulators led the U.S. Congress and President to delay taking appropriate action.

Looking at both MSB’s and S&L’s, it appears that

-- state-based usury laws were not pre-empted until the huge industry of mutual savings

banks for small savers was effectively bankrupt,

-- local and state mis-management threw S&L losses onto national taxpayers, and

-- national legislators were afraid to anger politically powerful state-based regulators.

So, is it true that taking responsibility could be avoided at both the state and the national level, by “respecting”, or “passing the buck to” the other level? Is that what happened? Higher savings interest rates certainly were delayed.

Even today, U.S. officials are aware of the lack of coherent national banking regulation, and of the dozens of other countries that have opted for one form or another of national control.[24]

I ask you: did this “dual”, state and national banking aspect of the federal structure of the U.S. contribute to our failing to provide enough indexing of savings interest rates against inflation?

Did we fail to provide enough indexing against inflation for Americans’ wages?

Since 1938, U.S. wages are supported by a U.S. national “minimum wage”. Unfortunately, U.S. law now allows Americans to be paid a national minimum wage so low that they can work full-time and still make an amount of money which is only 60% of the poverty level for a family of four.[25] OK, if they can find and afford day-care for the children, both parents can work and with two incomes the family can slightly exceed 100% of the poverty level. For 2008 definitions of the poverty level see [26].

Now, imagine that the income of each parent is our own income. The 2008 poverty level for a family of four is $21,834, so 60% is $13,100. If full-time work is 40 hours times 50 weeks, or 2000 hours per year, then $13,100 works out to $6.55 per hour.

In case the notion of “$6.55 per hour” is too abstract, let us make it more concrete. Eating fresh fruit is good for our health. At a nearby grocery store on July 5, 2010, fresh cherries cost $3.99 per pound.

So, ignoring taxes, after an hour of work for $6.55 we can buy a 1.65 pound bag of cherries. What is the minimum wage job that we are going to do for an hour, to earn that bag of cherries? Is it

-- laying out 80-pound bags of cement at a home improvement center, or

-- raking asphalt in the summer heat on a road repair project, or

-- filling french-fries containers at a fast-food restaurant?

Which of these jobs or other jobs are we willing to do for an hour, for one bag of cherries?

Do we think it is okay for people to work full-time and not be able to afford to raise a healthy family? If that is what we think, how will we maintain the U.S. labor supply for future generations?

If we do not eat healthy food, we do not live as long. If we do not live as long, should we start raising a family earlier, shortening our formal education? Is that how we should maintain the U.S. labor supply, with an unhealthy, shortened, less educated life style?

I had the good fortune to play interscholastic sports as a teenager and I remember the ballplayers from the poorest neighborhoods. They were every bit as smart, strong and skilled as we were.

If inadequate support for the minimum wage contributes to people leading shortened, unhealthy and less educated lives, this seems wrong on many grounds: it feels evil, it wastes people’s potential, and it increases people’s temptation to turn to alternative activities, for which they and we will pay a price.

Now, as bad as the situation with the national minimum wage is, the situation in the individual U.S. states is often worse:

-- 5 U.S. states have no minimum wage

(Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, South Carolina),

-- 5 U.S. states have a minimum wage lower than the national minimum wage

(Georgia, Arkansas, Colorado, Wyoming, Minnesota),

-- 26 U.S. states have a minimum wage only as high as the U.S. national minimum wage, and

-- 14 U.S. states have a minimum wage higher than the U.S. national minimum wage

(Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio,

Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maine).[27]

True, there are cost-of-living differences from state to state, and where local law, state law and national law have different minimum wage rates, the higher standard applies.

So we might be tempted to conclude that the situations in the 50 individual U.S. states do not matter. But could we be wrong?

Why wrong? Because it turns out that the U.S. national legislature includes a council of these same states, a council called the U.S. “Senate”.

And in this council, each state gets the same vote, whether its population is large or small. The range of size of U.S. state populations is enormous, currently 69:1 (California:Wyoming).[28]

We just saw that 36 states have a minimum wage less than or equal to the national minimum wage. And since there are 50 states, it follows that 36 states are 72% of the states, and therefore they get 72% of the vote in this national council called the Senate.

At the same time, according to the year 2000 census figures [28], the 36 least populous states have only 101 million of America’s 281 million citizens, i.e. only 36% of the U.S. population.

So, representing 72% of the states, although as little as 36% of the population, council members or “Senators” from 10 states with no or lower minimum wage, plus 26 states that only go along with the national minimum wage, could have an easy time dragging down the national minimum wage, if only by inaction in a time of inflation.

And fewer than 72% of the states, representing perhaps less than 36% of the population, could prevent a national minimum wage from being indexed to inflation. Under these circumstances, we might ask “Why would anybody even try?”

We could also focus within each state and ask: how many American cities have passed their own higher minimum “living wage”? The answer is more than 100.[29]

And remember that a city in one U.S. state can have a bigger population than a whole other state. For example, the city of Albuquerque, New Mexico, is only number 34 on the list of America’s biggest cities, and yet it has a population as big as the whole state of Wyoming.[30]

We could also ask: how many undocumented workers in America may be paid even less than the impoverishing legal national minimum wage? Here, statistics are more difficult to obtain, but the answer in 2005 was as many as 7 million workers.[31]

We should also note that individual cities or states are at a disadvantage in applying higher minimum wages because the argument is made that employers will move elsewhere.

So I ask you: did this state and national minimum wage aspect of the federal structure of the U.S. contribute to our failing to provide enough indexing of wages against inflation?

We may have no idea how many Americans would have wanted more indexing of savings interest rates or wages against inflation.

But we can certainly see how state-based power in banking did delay indexing of savings account interest rates, and now we see how, in the U.S. Senate, states with a minority of U.S. citizens can impede indexing of wages against inflation, if anybody bothers to try.

To sum up, it appears that we Americans had a good savings rate, and that it was destroyed by inflation plus the fact that we did not index savings interest rates and wages against inflation.

And what I see here is that the federal structure of the U.S. government has impeded and can continue to impede such indexing. But have any Americans benefited from this structure?

Our work doubled the economy but with record-breaking income inequality

It is time to return to the caveats about whether the money supply increased in real terms and what has been the distribution of any real benefits.

Since 1973, for the first time, the U.S. has tried a fiat currency, and we may not quite have done it right. Still, we can argue that taking the money off gold has been at least partly successful.

Why? Because work in the U.S. economy sustained an expanding economy.

As we saw in figures 3 and 4 above, since 1973, the M3 money supply increased by a factor of at least 10, while inflation increased the cost of living only by a factor of 5. This relationship is approximate, but the implication is that the economy has doubled in real terms. Here is an explanation:

Imagine the fraction of available dollars that each person has. Now imagine that the fractions remain unchanged but the total number of dollars increases, and that people go out to purchase the same goods and services.

The result tends to be fully proportional repricing. If the money supply increases by a factor of 10, prices tend to increase by a factor of 10. There is no reduction of price increases by spreading the money over an increased production of goods and services.

But fully proportional repricing is not what happened in the U.S. The money supply went up by a factor of 10, but prices only went up by a factor of 5. The implication is that the total amount of goods and services has doubled.

A doubling of the economy in real terms would mean that the money-based value of the U.S. economy has increased as much as the value of gold, which, as we calculated above, has also increased proportionally by about a factor of two.

Are you thinking what I am thinking? Work in the U.S. economy is as good as gold!

Not bad! What a bullish indicator this is, about work in the U.S. economy. Other fiat currency economies may have done as well.

But, to see how much individual Americans have benefitted, we need to take population expansion into account, and also the distribution of this real increase in the economy across the population.

The latest U.S. census numbers that I have are from 2000, not 2006, but I will work with them. From 1973 to 2000 the U.S. population expanded from 203 million to 281 million.[28] If the economy doubled in real terms, that means the economy went up in value per person by a factor of 2 * 203 / 281 = 1.44, or, on average, Americans as of the year 2000 were 44% better off than in 1973.

Now, what about the distribution of this approximate 44% benefit over the population?

Well, it has not at all been an equal benefit.

And in that regard, some would ask: if the country had been “handcuffed” by more indexing against inflation for savings interest rates and wages, would indexing have destroyed the ability of the U.S. economy to expand 44% per person in real terms?

But I would ask: could indexing have helped keep the U.S. from setting new record highs for income inequality?[32]

Who cares? Well, maybe we should all care. Advantages of less income inequality are extensively documented in a recent book.[33]

And extreme income inequality is not a necessary consequence of having a fiat currency.

Income inequality is not present to the same degree in all countries that have fiat currencies: the income share of the top 1% has risen to 15% in the U.S., but that is twice as high as in Switzerland, France, Japan or the Netherlands.[34]

Figure 6. In 2007 the top .01 percent of American earners took home 6 percent of total U.S. wages, a figure that has nearly doubled since 2000. Source: Huffington Post.[32]

Looking at figure 6, a natural question to ask is: is there something peculiar about the U.S., that explains why the top .01% of earners took home 6% of total wages in 2007?[32]

Since 1973, the U.S. economy seems to have gone up, on average, about 44% per person in real terms, but the income share of the top 1% has increased to 15 times the per person average, far more than in other developed countries, and the income share of the top .01% has increased to 600 times the per person average, not at all an equal distribution of the benefits.

So, reviewing the facts, we appear to have a tripling of national debt, destruction of the small savers’ savings banks, “pass-the-buck” between state and national officials until a $160 billion S&L bailout is necessary, an hour’s labor for a bag of cherries, and record income inequality despite work that doubles the economy in real terms.

At this point, how many Americans are asking “How do we make our system better?”

Questions for the future

If there is reason to be dis-satisfied, and if we want to move beyond blaming, to learning from and acting on the lessons from our first, partly successful move to a fiat currency, what questions should we be asking?

I would ask: who does the current U.S. “federal” government system benefit, if it supports an upward redistribution of wealth, e.g. by 1) indexing home mortgage interest rates more than the personal savings account interest rate or the national minimum wage, and by 2) tolerating record-breaking income inequality?

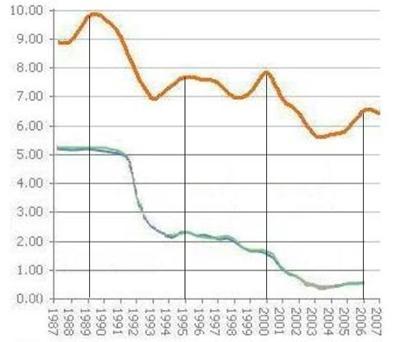

And just to be sure that we have a picture in mind of how well mortgage rates have been indexed compared to savings account interest rates, I have inserted Figure 7, below.

Please use this figure to compare mortgage interest rates versus personal savings interest rates during each bump-up in the mortgage rates since the 1980s. In 1989, we have 9.9% for mortgages, 5.1% for passbook savings. In 1995, we have 7.6% for mortgages, 2.3% for savings. In 2000, we have 7.9% for mortgages, 1.7% for savings. And in 2006, we have 6.4% for mortgages, 0.5% for savings.

In this time period, the mortgage-to-savings interest-rate ratio seems to have gotten more extreme: 2 times higher mortgage interest at the end of the 1980’s, 3 times higher at the middle of the 1990’s, 4 times higher in 2000, and 13 times higher in 2006.

Figure 7. Average contract mortgage interest rate (top) vs passbook and statement savings interest rate (bottom), 1987 – 2006. The mortgage-to-savings interest-rate ratio increases from 2:1 in 1989, to 3:1 in 1995, to 4:1 in 2000, to 13:1 in 2006. Sources: mortgage-x.com [35], bankrate.com[36].

Does this increasing ratio of interest-earned to interest-paid-out help explain why bankers and the finance industry were increasingly eager to market mortgages before the current recession?

Do the lack of indexing and the increase in economic inequality indicate that we need a change in the political system, to get better representation for ourselves economically?

Or, is this just “one little problem”, and if we change the political system for this little problem what are we going to do when the next little problem comes along, change the system again?

Personally, I wonder what kinds of changes in the U.S. political system might increase the chances for national indexing of savings interest and the minimum wage. I think such changes would support a distribution of the benefits of our partly successful fiat currency and national economy along lines of greater equality.

Possible answers for the future

I assume that we want our political system to be sensitive to the needs and talents of everyone.

And in that regard, when it comes to these economic issues, does it matter that large parts of the American population are downweighted in the process of selecting our national executive, the U.S. President? Does it matter that large parts of the American population are downweighted in the state-based U.S. Senate? Does it matter that large parts of the American population are downweighted in the state- and Senate-based constitutional amendment process?

Please forgive me if I sound like a broken record, but I have to point out, just as in previous discussions of healthcare [37] and education issues [38], that these economic issues lead me to the following questions:

1. What are the consequences of the U.S. government downweighting the 21 most

populous states so much in the selection of the U.S. President that these states'

effective loss of population, 64 million people, is greater than the entire population

of the rest of the country, which is only 63 million people?[38]

2. What are the consequences of the U.S. government downweighting the 16 most

populous states so much in the U.S. Senate that these states' 68% of the U.S. population

only gets 32% of the senate vote?[38]

3. What are the consequences of the U.S. government downweighting the 37 most

populous states so much in the U.S. constitutional amendment process that these states'

95.5% of the population can be blocked by a plurality of the remaining 4.5% of the

population?[38]

4. And if these consequences are on balance bad, is there any realistic approach

to a work-around?[38]

I am not sure if the reader can imagine what I mean by “downweighting”. If you have any questions, please look at paper [38], where I give details.

As far as I can tell, a good first step toward a work-around would be focussing on question 1, and passing the state-by-state compact called “National Popular Vote”.[39]

Let me end this section with two questions:

To do better on these economic issues which I would summarize as 1) not enough indexing and 2) record-breaking income inequality, do we have to change how we Americans govern ourselves?

If we did so, inspired perhaps by the above bullish story about work in the U.S. economy, where would we Americans find our next opportunities?

More questions and answers and a conclusion

I have discussed these issues with enough people to have begun to expect certain questions. Here are six of those questions and my answers to them.

Q1: Other countries do not have the American federal structure or the extreme nature of America’s indebtedness or savings crisis, and yet they do not have indexing either. Why assume that we must have indexing to solve these problems, or that the American federal structure is peculiar in impeding indexing?

A1: Indexing is a way to support the wage-earning and wage-saving public while money is being paid. Some countries provide support after money is already in hand, for example with a tax on assets.

The U.S. does have taxes on assets at the local and state levels. If we have a more expensive home in the U.S., we pay a higher local property tax and support the local public school. In some U.S. states, if we have a more expensive car, we pay a higher registration fee and support state services.

Note that we pay these local and state taxes on assets over and over again. Year after year, we pay taxes on assets that have already been taxed. And what do we get in return? Most importantly, we get a local public school, or a public, state university, each of which educates the next generation of wage-earning and tax-paying citizens.

But at the national level, the U.S. has no tax on assets. This year, the U.S. does not even have a tax on the inheritance of assets.[40] This is a way of saying that at the national level “wealth does not need to contribute to commonwealth”. I think this is peculiar.

And the U.S. has only a tiny tax on revenue from assets. Revenue from assets, so-called “capital gains”, is officially separated from “income” and is taxed at a lower rate, not more than 15%.[41]

Indexing is one alternative for supporting the public. It is not the only alternative. It could be used in combination with a national tax on assets and perhaps other alternatives.

With respect to the U.S. federal structure, that structure is based on enormously different populations across same-weighted jurisdictions called “states”. Is the use of same-weighted jurisdictions, regardless of population, peculiar and also anachronistic? I think so. It is inherited, like the U.S. Electoral College, from the Holy Roman Empire.

Ever since the Golden Bull of 1356 and until the Holy Roman Empire was overthrown in 1806, the vote of the duke from any jurisdiction that helped select the Holy Roman Emperor was given equal weight, no matter how few or how many subjects that duke had.[42] This practice was copied in the U.S.’s same-weighted senators and same-weighted senatorial electors.

In this aspect of our self-governance, here in the year 2010, Americans are treated unequally by state-based representation at the national level, like the subjects of an empire that has been dead for 200 years. I think this is peculiar and anachronistic. With the banking examples above, I have already demonstrated how I think our federal structure impeded and impedes indexing.

Q2: What is the evidence that indexing of interest rates and wages would be economically viable?

A2: This question is at the heart of the matter. In the case of savings interest, we are paying someone for the use of their money. In the case of the minimum wage, we are paying someone for the use of their labor. We should not cheat a person in either case.

We would have to be careful to index savings interest and the minimum wage in an on-going way, indexing either up or down, based on some time-varying quantity that we can treat as an independent variable.

The independent variable is different in each case. In the case of money, the adequacy of interest rates depends on the cost of borrowing, e.g. the U.S. “Federal Funds” rate. In the case of labor, the adequacy of a minimum wage depends on the cost of living, e.g., to a first approximation, the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

The corresponding dependent variable, our savings interest or our minimum wage, could be indexed up or down by some fraction of the change in its independent variable.

For example, suppose we are indexing by a full 100% of the change in the independent variable. If the funds rate goes up or down by, say, 5%, then our savings interest would go up or down that full 5%. If the cost-of-living goes up or down by say, 1.4%, then our minimum wage would go up or down that full 1.4%.

Note that this proposed indexing of the minimum wage is different than the indexing of Social Security in the U.S., with its “cost-of-living-adjustment” or “COLA”. Social Security gives us some base payment plus no COLA or some COLA, depending on the change in the CPI.

If the cost of living goes down, our base payment from Social Security is not reduced, but I would argue that our minimum wage should be reduced. Of course, we have paid into the Social Security trust fund, so Social Security is different.

In my opinion, an ongoing responsibility for indexing follows from our decision to move to a fiat currency. At the national level, we should not take the authority to act on how much money there is, and thereby influence what the value of money will be, without also taking the responsibility to protect people if necessary from the consequences of our actions.

So one question is: what fraction of the change in the independent variable should indexing provide?

If we index by a full 100% and the cost of borrowing goes up, then our bank would be paying us the same percentage increase that it itself is charged for new borrowing from elsewhere. Some of our bank’s borrowing does not come from our savings accounts. If it is economically viable for the bank to pay a certain percentage more to borrow from others, is it economically viable to pay the same percentage more to borrow from us?

Next, consider our minimum wage. If we index by a full 100% and the cost of living goes up, then our employer would be paying us the same percentage increase that it hopes to be able to pay to other employees when the cost of living goes up, to avoid employee dissatisfaction, departure or termination. If it is economically viable for our employer to pay a certain percentage more for the labor from those who earn more than the minimum wage, is it economically viable to pay that same percentage more for those of us who earn only the minimum wage?

Note that our economy is a system with feedback, where previous outputs are part of following inputs, after some amount of delay. It is possible that too much indexing, applied too quickly, could contribute shortly thereafter to sending the economy in the opposite direction, in particular, down when we expected to share in going up.

So, people who worry about whether indexing might “handcuff” the economy could have a point.

Suppose we demanded, say, 200% indexing, or 500% or 1000%. Rather than enabling us to share in increased interest payments or increased wages, too large an amount of indexing might decrease the interest or wages available, and contribute to economic instability or reversal.

And, what happens if we demand too much indexing and the independent variable goes down? Would we be happy if our interest or minimum wage is indexed to go down twice as much, five times as much or ten times as much as the independent variable?

On the other hand, what happens if we demand too little indexing? If the cost of borrowing and the cost of living tend to move in one direction, slowly growing and expanding, and we demand less than 100% indexing, our interest payment and wage fall further and further behind.

So, is there a quandry here? Is indexing of interest or wages unsatisfactory by any fraction other than 100%, but 100% does not work and that is why no country uses it?

No, the solution for indexing of personal savings and the minimum wage does not have to be “no indexing”.

The solution can be to apply indexing gradually. For example, we could apply half of the desired 100% indexing, twice as often, say, half of the past 12 months’ change in the funds rate and half of the past 12 months’ change in the CPI, twice a year.

In this way, indexing would follow or track the changes in interest or wages, but not reverse them. It would lag, but not increasingly fall behind.

The details would need to be worked out carefully. But with our current “federal” political system, would anybody even try?

On the issue of economic viability, it is possible to construe economic viability narrowly, e.g. as 1) a commercial issue of supply and demand for different sources of money or labor, or as 2) a struggle between equilibrium or market prices and indexed or legislated prices.

But perhaps we should view economic viability more broadly, as an economic and political issue of at least national scope, an issue where we try to match economic authority with economic responsibility.

From this broader point of view, we should ask: what is the evidence that not indexing is economically and politically viable? According to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency:

the U.S. has one of the most unequal income distributions in the world.[40]

And according to Citibank’s Equity Group:

the top 1% of American households account for 40% of financial net worth,

more than the bottom 95% of households put together.[34]

So, our current system has brought us to a tripling of national debt, no personal savings, and extreme inequality of both income and net worth.

From this broader point of view, is our current system sufficiently economically and politically viable, or does it need to be made more economically and politically viable?

To come to the second part of the question, suppose it is true that, without indexing, other countries have succeeded in finding at least partly viable solutions against 1) the loss of savings and wages and 2) extreme inequality of income and net worth.

I would ask: is any of these supposedly successful countries impeded by a national system that is as unrepresentative as the U.S. federal system? For example, do any of these supposedly successful countries have 69:1 discrepancies in the representation of their citizens nationally?

If such other countries use a tax on assets, or other tax alternatives, are these alternatives to indexing fully satisfactory or only partially satisfactory, either in principle or in practice?

Without giving up on my preference for indexing, I agree that it would be worthwhile to contrast the U.S. and other countries at greater length on the matter of alternatives to indexing, e.g. on taxation. It is conceivable that we could protect after the money is in hand, in addition to or instead of protecting while the money is being paid.

Q3: Are you closing the barn door after the horses ran away? Your 4.35% inflation is a thing of the past. In the current extreme recession, inflation is not the issue, deflation is the issue. How is indexing savings interest going to help us in deflation? Interest is a positive quantity only, we cannot lower an interest rate below zero. This is the U.S. Federal Reserve’s current problem.

A3: First, I have confidence that some amount of deflation and associated debt reduction can be good for us. If we have “overheated” the economy and created a “bubble” of activity, we can now slow down our purchasing of at least certain goods and services and make less of at least certain goods and services, while we improve our national and personal balance sheets.

Japan is sometimes cited as a recent example of bad aspects of deflation. But during the worst of its recent deflation, Japanese unemployment apparently did not rise above 5%.[43] If any amount of deflation must be very bad, how did Japanese employment hold up so well?

Second, to fight extreme deflation, the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank can make an inflationary move any time it wants.[44] One obvious move is to monetize the U.S. debt. “Monetizing the debt” means paying for U.S. debt obligations from money invented for the purpose.

For example, suppose countries and pension funds cut back on their purchase of U.S. debt obligations. If our U.S. government cannot find enough buyers for its debt obligations, it cannot keep operating. First, its credit rating would fall. This is already happening.[45] And then it could go into default, like Russia did in the 1990’s or like Greece almost did this spring.

Fortunately, thanks to the fact that we took the U.S. dollar off gold, the Fed can now step in and buy those debt obligations, by just saying that it has the money. By inventing the money. By fiat.

Normally, monetizing the debt would be avoided because it is too inflationary. It instantly gives us more money without more goods and services. We are back to the scenario of fully proportional repricing.

And, by adding a lot more money, the Fed could create hyper-inflation. Inflation rates of more than 4.35% could be upon us very quickly.

So there is danger as well as power in monetization, but I am not worried about deflation. I believe the Fed can chose the timing and the amount of its actions to limit either deflation or inflation.

Q4: It is one thing to blame the interplay between the U.S. states and the national government for a failure to index. But surely indexing could also fail with the national government alone in charge.

A4: I agree. But I think the chances of failure at the national level are reduced if we have economic and political sensitivity to all of the country’s population. This is something that we do not have under our current federal system. Instead, in the selection of the national executive and in our national council of states, we have same-weighted representation for enormously different populations.

What I think we need is voting proportional to population in the selection of the national executive, and voting proportional to population in any chamber of the national legislature.

Q5: Wow, that is quite a leap. Why jump from finger-pointing between state and national banking regulators all the way to changing how we select our president?

A5: The history of keeping responsibility for banking within the states is related to the history of keeping responsibility for selecting the national executive within the states.

Having the same representation for each state in the council of states aka the U.S. Senate, regardless of population, keeps us tied to state-based banking. Similarly, having the same representation for each state with two senatorial electors in the U.S. Electoral College, regardless of population, keeps us tied to a state-based national executive.

Do we need a reminder of the kinds of things that happen because of the current process for selecting the U.S.’s state-based national executive? If so, we should review the events:

1. in Florida in 2000, where a state awarded the highest political office in the country to a

candidate who lost the national popular vote, while justices on the highest national court

pointed out that U.S. citizens do not have a constitutional right to vote for their national

executive; and we should review the events

2. in Ohio in 2004, where, among other things, a state official decreed that citizens’ voting

registrations could be rejected if they were not printed on heavy-enough paper.[46]

I mean, really, would you tell me that we cannot or should not do better than this?

In my opinion, getting rid of the state-based national executive is something that we should have done long ago. If we only now realize that it may be time to get rid of 50 state-based banking systems as well, we are playing catch-up.

And, just as bad, perhaps, are our 50 state-based insurance regulation systems. Most Americans are not aware that there is only state-based insurance regulation, no national insurance regulation in the U.S.[47]

This fact is the reason why 20 U.S. states (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, North Dakota, South Carolina, South Dakota, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah and Washington) have joined in a lawsuit against the U.S. national government for recently passing a U.S. national healthcare insurance law.[48] Yes, a 21st state, Virginia, is suing as well, but that is because Virginia rushed through a law claiming to exempt itself from national fines for not having health insurance.

If you are the head of insurance giant AIG, you may find the existence of 50 inconsistent, less-informed and less-powerful state-based insurance regulation systems to be a good thing. If you are a U.S. national taxpayer forced to bail out AIG in the amount of $85 billion, you may have another opinion.[49]

So, whether we are talking about problems of state-based banking, state-based minimum wage, state-based insurance or state-based national executive, my opinion is that these problems have a common origin, and should all be addressed constructively by taking a national approach.

Q6: Is it ironic that you would implicate the 50 individual U.S. states in a failure to index for inflation, and then turn to a state-based compact to pass “National Popular Vote”?

A6: It may be ironic, but inter-state compacts are there for us to take advantage of. Once we understand that the state- and Senate-based U.S. constitutional amendment process is the normal way of not changing the U.S. Constitution, we can understand that the initiators of National Popular Vote had no choice. To learn more about the history of having to go to states to get national reform, please see Responses to Myths about the National Popular Vote Plan, reference [50].

In conclusion, I believe indexing is useful for describing both how we lost our savings habit, and how we might get it back. I may, however, have put too much emphasis on my preference for indexing, too little emphasis on how to implement indexing, and too little emphasis on alternative approaches such as taxation.

Some people may claim that the price of gold has “gone through the roof” and that the U.S. economy has “fallen apart”. I am pleased to be able to argue that since 1973, gold has gone up by only a factor of two, and that in the same time period the U.S. economy has also grown in real terms by a factor of two. I am pleased by this partly successful implementation of our new, fiat currency.

But I am troubled by the inability of our surprisingly unrepresentative “federal” system to provide adequate indexing. And I am troubled by our extreme inequality of income and net worth.

My question now is, to do better on indexing and on equality, do we in the U.S. need to change the way we govern ourselves?

Are these facts and questions any help? What have I missed? What are your thoughts?

References

[1] U.S. National Debt Graph: Since Great Depression

[2] High Ratings at Risk for Big Economies

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/16/business/global/16rating.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

[3] History of the United States dollar

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_United_States_dollar

[4] Gold soars to fresh closing record

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/gold-futures-runs-towards-fresh-record-levels-2010-06-18

[5] Money supply

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply

[6] Looking back, ahead at federal taxing, spending

http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/tax-rates-spending.htm

[7] What Caused the Financial Turmoil – Editorial Part 1

http://libertysilver.se/articles/finansproblem

[8] Are REITS Right for Your Portfolio?

http://www.themoneyalert.com/REITArticle.html

[9] CPI's Lie on Household Inflation Doesn't Wash

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a2SUCQ3Bslk0

[10] Honohan, Meet Havenstain

http://dailyreckoning.com/honohan-meet-havenstain/

[11] Views of retirement waver

http://www.seniormarketadvisor.com/Issues/2008/4/Pages/Views-of-retirement-waver.aspx

[12] Find the Best Savings Accounts

http://www.money-rates.com/savings.htm

[13] 15 Mind-Blowing Facts About Wealth And Inequality In America

[14] 10 Year U.S. Treasury Note Yield Forecast

http://www.forecasts.org/10yrT.htm

[15] Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergency_Economic_Stabilization_Act_of_2008

[16] Obama: Stimulus lets Americans claim destiny

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/29231790/

[17] Hedge Funds: Very Short 10 Year Treasuries

http://www.marketfolly.com/2010/05/hedge-funds-very-short-10-year.html

[18] Historical Graphs for Mortgage_rates.htm

http://mortgage-x.com/trends.htm

[19] New foundations for home financing

http://www.lib.niu.edu/1980/ii801217.html

[20] Greenbackism and Peter Cooper

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper/Parrington/vol3/bk02_01_ch01.html

[21] A 1930-33 based model for evaluating states' branch banking laws in the U.S.

http://www.allbusiness.com/north-america/united-states/569794-1.html

[22] The Mutual Savings Bank Crisis

http://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/history/211_234.pdf

[23] Savings and Loan Crisis

http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/SavingsandLoanCrisis.html

[24] FDIC Banking Review

http://www.fdic.gov/bank/analytical/banking/2006jan/article1/index.html

[25] Minimum Wage History

http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/anth484/minwage.html

[26] Appendix B. Estimates of poverty.

http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p60-236.pdf

[27] Minimum Wage Laws in the States - January 1, 2010

http://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/america.htm

[28] List of U.S. states by population

http://www.nationmaster.com/encyclopedia/List-of-U.S.-states-by-population

[29] Effective Tax Rates and the Living

Wage

http://epionline.org/study_detail.cfm?sid=81

[30] List of United States cities by population

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_cities_by_population

[31] Number of undocumented workers by state and their workforce share

http://www.workingimmigrants.com/2006/02/number_of_undocumented_workers.html

[32] Income Inequality Is At An All-Time High

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/08/14/income-inequality-is-at-a_n_259516.html

[33] Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett. 2009. The spirit level: why greater equality makes

societies stronger. New York, Bloomsbury Press.

[34] Citigroup Oct 16, 2005 Plutonomy Report Part 1

http://jdeanicite.typepad.com/files/6674234-citigroup-oct-16-2005-plutonomy-report-part-1.pdf

[35] Interest Rate Trends

http://mortgage-x.com/trends.htm

[36] Historical chart of savings rates

http://www.bankrate.com/brm/publ/passbkchart.asp

[37] From the JUPITER Crestor study: competing hypotheses, life-style changes, and potent

compounds available in our foods, to an opportunity for health-care reform and many other

reforms needed in the US

http://www.stmartinsystems.com/090309_for_Majid_Ali.htm

[38] The 2007 US Chamber of Commerce Education Report Card, a political Pandora’s box, and

a democratic opportunity for US business

http://www.stmartinsystems.com/070831_US_CofC_education_report_card.htm

[39] National Popular Vote

http://www.nationalpopularvote.com/

[40] How the rich are winning

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/the-recession-is-over-the-rich-won-2010-07-20

[41] Capital gains tax in the United States

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capital_gains_tax_in_the_United_States

[42] Golden Bull of 1356

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Bull_of_1356

[43] That big sucking sound in the economy is the threat of serious deflation

[44] Fed to mull stimulus moves just in case

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/fed-to-mull-stimulus-moves-just-in-case-2010-07-14

[45] Sovereign Credit Rating Report of 50 Countries in 2010

http://www.dagongcredit.com/dagongweb/uf/Sovereign Credit Rating Report of 50 Countries in 2010.pdf

[46] Bush v. Gore

http://www.answers.com/topic/bush-v-gore

2004 United States election voting controversies

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2004_United_States_election_voting_controversies

[47] The U.S. Federal Financial Regulatory System:

http://www.fdic.gov/bank/analytical/banking/2006jan/article1/index.html

[48] States joined in suit against healthcare reform

http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE64D6CJ20100514

[49] U.S. to Take Over AIG in $85 Billion Bailout

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122156561931242905.html

[50] Responses to Myths about the National Popular Vote Plan

http://www.every-vote-equal.com/pdf/EVECh10new_web.pdf

[ 100814_Why_did_we_Americans_lose_our_savings_habit.htm ]